How To Take Your Fencing To The Next Level

New students often tell me that they don’t know what to do next while fencing, so I’ve been thinking about how to explain this for a while.

This past weekend I was at a broadsword seminar run by Broadsword Academy Manitoba where guest Kevin Cote gave a talk about the exceptionally confusing tactical wheel of fencing and simplified it into something similar to this less confusing tactical fencing wheel (this is not the same, though it is similar in many ways) of fencing and how it applies to historical fencing weapons. This got me thinking about doing something similar with my understanding of fencing.

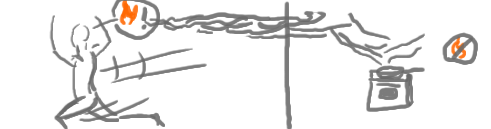

Kevin did a lot to simplify the wheel that I linked to, but I wanted to cut it down to it’s bare essentials and came up with this

The wheel of fencing goals (x->y means x counters y)

I should point out that this deals with the goals of a fencer, and how those goals manifest. We should view the technique that they have chosen as the manifestation of their goal within the specific scenario occurring in the fight at that exact moment.

The idea is that you start in the Zufechten (prefencing) before any action is taken by either person, then one person chooses an action, an attack for example, and the opposing fencer must choose an action that beats their action.

Some examples of a free attack:

Abnehmen

Ansetzen

Durchgehen

Durchwechseln

Soft Winden/ Duplieren

Schnappen (when close)

Really any attack where you change from one side of the opponent’s blade to the other. This is specifically relevant with the initial attack, and from the bind when someone decides to move from one side to the other. Normally if you do an attack where your hilt goes from one side of your body to the other, it fits in here. With a thrust oriented weapon it would be any form of disengage and doesn’t necessarily require a follow up attack, though you should expect one

Examples of controlling the center:

Hard Winden

Constrained cut (attacks that do not change side)

Mutieren

Counter Cut

Parry

Actions that control the center are normally done by getting the strong of you blade between the opponent’s blade and their target. The goal is to prevent them from hitting you by using a barrier, either you blade or a shield, or some other object to stop their cut as it comes on line. Again these are conceptual categories not specific to any weapon, so you should just fill this in with whatever options are available with the weapon you are using.

Examples of displacing the opponent off the centerline

Pogen (with messer)

Cross knock from Zwechhau

Most of the displacing cuts in Fiore

Parries that go wide and don’t threaten the opponent with a thrust/cut

Stepping off the line

This is really any action where you force the opponent’s blade to the side, usually with the intention to side usually with the intention of following up with an attack. However it also includes lateral movement where you move the line such that the opponent’s blade is no longer aimed at you.

These categories form a kind of rock paper scissors that should help you understand the category of attack to use in a situation, and figure out which situation your opponent is putting you in.

I should point out that it is not helpful to try and memorize lists of technique names and compare them to a list of other techniques. This is about understanding what the opponent’s goal is in terms of how they will handle the fight, and some actions (eg the winden) can actually be used in multiple of these situations depending on what they accomplish.

Some examples of how a play might go:

You begin in Zufechten, the opponent cuts to your upper right opening (free attack), you counter with an Absetzen to the upper right hengen (controlling the centerline), the opponent displaces your blade to the left (displacing off centerline) and closes in with a cut to your upper right opening (attacking freely). At this point the best option is to once again control the center, this time with a Zwerchau to the left upper Hengen to hit them in the head on their left.

The last bit happens regularly, but often people choose to counter the displacement into cut with a displacement of their own, causing a parry-cut game. Doing the Zwerchau style Abschneiden actually beats their movement more conclusively by keeping your blade on the same side and smothering their action before it has it’s intended result. Alternatively if they managed to cut around and get to the other side of your blade you would still use the same concept but it would manifest differently, this time cutting down onto their blade so it forces it down and onto your strong as you cut down and if you haven’t hit them thrust (a Mutieren).

Another Example with rapier:

Your opponent is in a guard (controlling the center), you thrust directly at their head (Freely attacking) that slides off to the side and your opponent thrusts you on recovery (constrained attack from a controlled center).

Since they have the center controlled from the beginning with their guard, they don’t have to do anything other than attack you since they already have your blade under their control. Even though you aren’t changing sides, this would still be a free attack, you have just been deceived into thinking there is an opening when there wasn’t one, as they have controlled the center from the beginning, and the first attack from the Zufechten (the pre fencing) is always a free attack since you haven’t actually made contact, and thus you aren’t definitely on one side of their blade or another until the blades actually cross.

A slightly better approach:

Your opponent is in a guard (controlling the center), you feint a thrust and they over commit to their parry (displace your blade) so you disengage and thrust them to the other side, of course reorienting your blade to guard against a possible counter thrust.

This dips into the next level, but can be interpreted purely at the level of goals, they intended to control the center, your feint tricked them into changing from controlling the center to displacing you which created the opening you needed to thrust. You can see that many of the best actions in fencing also combine several of the core goals as well, such as the disengage (free attack) to the thrust from guard (controlling the center). Often times this is why these wheels end up getting so complex in the first place.

Your goal should always be to do an action that counters what they are doing at that instant, as well as defeat their likely followup actions as well. That being said I don’t think creating hybrid categories is as useful as understanding the most simplified goals and seeing how you can do more than one thing with one action, since that is really the key to developing good fencing in the first place.

It is actually not uncommon for people to jump around in this wheel, but every time they choose an action that doesn’t defeat the goal of your action they leave an opening for you to exploit. And that’s really what this is useful for, understanding where openings occur so that you can exploit them.

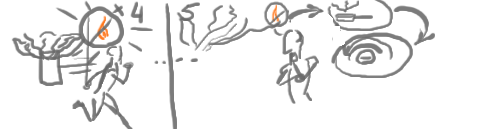

The next level of fencing comes down to the psychological portion of fencing, ie dealing with the opponent’s intent rather than their actions.

The wheel of fencing intentions

By attack I simply mean any committed attack that isn’t designed to stop an opponent’s action such as:

A direct cut or thrust to an opponent’s opening

cutting around to the other side to a new target

Really any action where you aren’t trying to stop the opponent from cutting you before your attack lands, even if you are trying to prevent probable attacks that occur after you launch your attack. This starts to deal with timing since you would predominantly do this when you have initiative, that is any time your opponent isn’t already attacking you.

A Counter is any action that is designed to stop an opponent’s attack that is already in motion, that would hit you were you to do nothing. Some examples include:

parries

counter cuts/thrusts

literally any defensive action that causes their attack to fail, even if it is the form of some cut or thrust of your own

A feint is any attack that is not designed to hit the opponent, but instead draw out an action for you to exploit. A feint can, and should, become a dedicated attack the instant you realize the opponent isn’t reacting. In essence it is a form of deception that causes the opponent to react and allows you to either attack them directly, or counter their action.

Here are some examples of plays examining their intention:

Your opponent is in a guard (intention to counter), they have done several feints previously and you believe that they are going to disengage and thrust from the other side (feint) so you thrust directly at their head (Intention to attack) guarding against the thrust you expect from the other side, your thrust slides off to the side and your opponent thrusts you as you recover (the counter attack works).

This situation seems incredibly stupid from the previous level of analysis (what to do technique wise), but it starts to make a bit more sense when we look at it in terms of psychology. In many ways the point of this is to disrupt the opponent’s intentions with deception until they can’t tell whether you will attack, counter, or feint.

This is my best attempt at distilling what I have seen over the past several years of fencing and martial arts in general, and using it to help inform people to make better decisions in their fencing.